Core Training - What is it? - Where do I start?

A prone bridge may be a great exercise to target the muscles of the core, but is it right for everyone? It is important to consider the muscles and structures that make up the core and the varying postures of clients when designing exercise programmes to develop core strength and stability.

Many clients will come to you straight from the office where they have been cooped up like a caged chicken for hours.

You can picture them there, spine slumped, shoulders hunched up around their ears and chins jutting forward as they peer at their computers. If the “core” is the centre of the body you can imagine for these clients, it will not be in a good condition. It will have been squashed, weakened and immobile for most of the day.

For this client the key components to core conditioning should be to lengthen, strengthen and mobilise. By looking at the structures that make up the core and what they do, you can decide the best way to improve your client’s current core condition.

What is the Core?

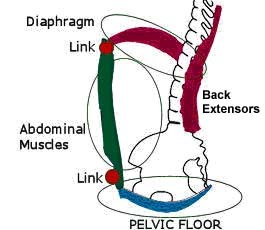

The inner core: is the soft bit between the ribs and pelvis. The inner core is what you’re thinking of when you want to get a six pack or protect your spine when lifting heavy loads. It’s a bit like a cylinder made up of the diaphragm at the top, the pelvic floor at the bottom and the abdominals and back extensors making up the walls.

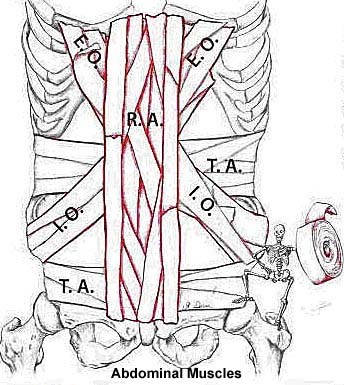

The muscles

that make up the walls wrap the abdomen in horizontal, vertical and diagonal

directions in the same way that packing tape is wrapped around a box. The

following diagram shows how the arrangement of these muscles provides strength

to the core and mobility to the spine. From the deepest level, the Transverse Abdominus

(TA) wraps horizontally, the Internal Oblique’s (IO) and the External Oblique’s

(EO) wrap diagonally and Rectus Abdominus (RA) runs vertically.

The muscles

that make up the walls wrap the abdomen in horizontal, vertical and diagonal

directions in the same way that packing tape is wrapped around a box. The

following diagram shows how the arrangement of these muscles provides strength

to the core and mobility to the spine. From the deepest level, the Transverse Abdominus

(TA) wraps horizontally, the Internal Oblique’s (IO) and the External Oblique’s

(EO) wrap diagonally and Rectus Abdominus (RA) runs vertically.

This arrangement allows the spine to bend forwards, backwards, side to side and rotate. Movement of the spine in all directions is import for maintaining the health of the inter-vertebral discs and digestive system as well as to keep the spine mobile. Contraction of these muscles also compresses the abdomen providing a natural girdle that lengthens and supports the spine.

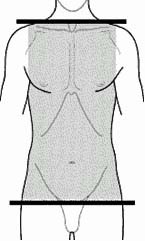

The outer core is the trunk, from shoulder to shoulder and hip to hip. The bones of the shoulder girdle, ribs, spine and pelvis protect the internal organs within and also act as attachments for the muscles that join the limbs and head to the body.

The pectorals, trapezius, rhomboids, latissimus dorsi, gluteals, hip flexors, abductors and adductors are the main muscles of the outer core. The trunk is like a rectangular box. It opposite sides should be parallel and its length and width should be maintained.

When the muscles of the inner core are evenly balanced they help to keep the trunk upright and maintain the length and natural curvature of the spine (see ideal posture on diagram).

If the inner core muscles are weak the muscles of the outer core can tighten up to provide stability to the spine, pelvis and shoulder girdle. You can often see this in people’s posture where tight hamstrings may pull the pelvis into a posterior tilt (see flat back diagram).

Another example is when tight hip flexors pull the pelvis into an anterior tilt (see Kyphotic - Lordotic diagram). As the brain tries to keep the eyes level with the horizon, a weakness on one side of the body results in tightening of the opposite side to keep the view level. The “normal” curves of the spine get pulled out of balance. If the brain didn’t do this the person with anterior tilt would be looking at the sky. To compensate the body rounds the shoulders to keep us looking straight ahead

With all this in mind, it makes sense that a core conditioning programme needs to include exercises that will get the spine moving, uses all the muscles of the inner core appropriately and also strengthens and stretches the muscles of the outer core.

Look at your client’s posture and see if it fits into one of the categories above. The next article will then tell you where to start working on it. If their posture isn’t ideal maybe they’re not ready for prone hold yet!

In my next article/video link I will give examples of exercises you can use to mobilise the spine, a continuum for inner and outer core abdominal exercises and methods for lengthening tight muscles of the outer core.