The knee explained [article]

The first article will look at each of these areas to help you understand what the knee is made up of. The aim is to give you a better understanding of a healthy knee before we look at injuries.

| Knee joint |

Knee ligaments |

|---|---|

|

|

The knee is the largest joint in the body and joins the two largest bones in the body, the femur and tibia. It is also the most commonly injured joint.

The reason for this is that the articulating bony surfaces (ends of the femur and tibia) don’t form a very deep bony socket. As a result the knee relies mainly on ligaments and muscles for its stability.

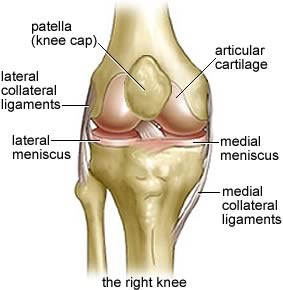

The knee joint is formed by three bones, the femur above the joint, the tibia below and the knee cap (patella) in front of the joint. Each bone is covered by a shiny white articular cartilage which aids smooth friction free movement of the joint.

Within the joint the bottom surface of the femur, known as the condyle is convex (bulges out), while the upper surface of the tibia, also known as the condyle, is slightly concave (like a shallow cup). This allows the femur to sit in a shallow socket. To deepen the tibial condyle sockets and help with stability, the surface of the tibial condyle is also covered by two fibrocartilaginous discs, the medial and lateral meniscus. These menisci are half moon (C) shaped and act as shock absorbers between the femur and tibia.

The anterior (front) of the knee is protected by the knee cap (patella), where its surface fits on the slightly concave surface (see patellofemoral groove on diagram) of the lower end of the femur. The patella lies within the quadriceps tendon (above) and the patella ligament (below), and protects the knee joint during movement. When the quadriceps contract and relax moving the knee cap up and down the lower end of the femur the knee cap protects the joint opening on the front of the knee.

The major bones of the knee are united and enclosed by a capsule which contains synovial fluid lubricating the joint and allowing the bony surfaces to move freely without any friction. Within the capsule we also have sacs filled with synovial fluid called bursae. Bursae are generally situated between tendons and the bones they run across and their role is to cushion and protect surrounding bones and tendons from friction during movement.

Ligaments

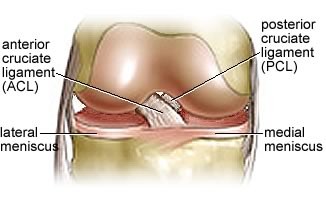

Within the joint capsule are the two major ligaments in the knee. They are located between the medial and lateral pairs of condyles and cross-over one another forming a strong X shape. They provide stability to the knee during movement.

The ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) attaches on the front of the tibia and stretches up and backwards to the back of the femur preventing any excessive forward movement of the tibia on the femur. If it wasn’t there the femur could slide backwards off the tibia.

The opposing ligament to the ACL is the PCL (posterior cruciate ligament). The PCL is a larger ligament and is attached to the back of the tibia and passing up and forwards to attach to the front of the femur preventing any posterior movement of the tibia on the femur. Basically it stops the femur sliding off the front of the tibia.

Outside of the joint capsule lies the supporting collateral ligaments which are located on the lateral and medial aspects of the knee and prevent side to side movement of the joint.

The medial aspect (inside) is supported by the medial collateral ligament, MCL (also known as the tibial collateral ligament) which protects the knee from inward acting force (valgus-force), imagine a tackle to the outside of the knee. The MCL is a flat band which runs from the medial femoral epicondyle (inside bottom of the femur) down to the shaft of the tibia attaching to the capsule and medial meniscus.

The lateral aspect of the knee is supported by the lateral collateral ligament (also known as the fibular collateral ligament), which protects the knee from outward acting force (vagus-force); imagine a tackle to the inside of the knee. The LCL is rounder, narrower and not a broad as the MCL and attaches to the lateral epicondyle of the femur (outside bottom of the femur) stretching down to the head of the fibular.

The ACL, PCL, Medial and Lateral ligaments of the knee provide the majority of stability to the knee joint when movement is generated by the surrounding muscles. As a hinge joint this movement is primarily along one plane, the sagittal plane (backwards and forwards). The knees primary movements are flexion and extension.

Movements and Muscles

Flexion is controlled by the hamstrings (semi-mebranonsus, semi-tendinosus and biceps femoris), with some help from gracillis, satorius and gastrocnemius. Extension is controlled by the quadriceps with some help from tensor fascia latae. It must however be noted that when the knee is in a flexed position, the knee joint also allows a small amount of internal rotation due to activation of semi-membranousus, semi-tendinosus, gracilis and satorius muscles, while external rotation is primarily caused by the biceps femoris muscle.

Summary

This article is to work as a reference guide for you – to help you understand a healthy knee so that you can better understand an injured knee. Now that we understand how the knee joint maintains its stability, the following articles will explore the most common injuries to the knee joint along with the general guidelines for rehabilitation.